This project is complicated: aggressive dates, multiple rework, and hours that accumulate. We would have liked to be more efficient between our results and our efforts, part of the definition of quality.

We can even imagine thinking: “with 30% of the project budget allocated to quality, it would be much easier; a better definition of the requirements, tests giving us rapid upstream feedback”. The reality is far from it.

It is not enough to arbitrarily allocate time, especially since business constraints do not allow it. “How to negotiate a project budget allocated to Quality?” was the theme of our round table suggested by Arnaud.

Join the QE Unit to participate in upcoming events or suggest topics. This event brought together the following participants whom I would like to thank for their participation, contributions, and proofreading of this article:

- Arnaud Dutrillaux, Senior Quality Engineer @ La Javaness

- Emna Ayadi, Testing Consultant @ Sogeti

- Julien Barlet, Senior Engineering Manager @ Decathlon

- Zoé Thivet, Application Test specialist @ Hightest, New Caledonia

This article is inspired by the problem-solving process part of the Quality Engineering methods, from the why to the iterations:

- Why have to negotiate a quality budget?

- Prepare a negotiation upstream of collaborative workshops

- Align the stakeholders around common interests

- Define the measures of value to be followed in the iterations

- What to do when the negotiation seems closed?

- The negotiation mistakes to avoid

Titles leave clues as to practices to put in place. If they seem far from the pure negotiation of a quality budget to you, it is normal; this is not the first subject to address.

Let’s start by identifying the why.

Why negotiate a budget allocated to Quality?

The Start With Why principle allows us to follow the problem-solving steps, starting with the why. Combined with the 5 Why methodology, we can explore the real priorities: the root causes.

Wanting to negotiate a quality budget implies its initial non-existence. Why is the budget not affected? Quality is not a priority. Why? It is neither understood nor defined. Why? Quality attributes were not expressed. Why? Quality is subjective and was not shared between the different actors. Why? The actors did not collaborate to align a common vision of quality.

This conclusion is already beneficial to us on the priorities to explore. We could also carry out the same exercise on why allocate a budget to quality. The shortcut to the 5 whys brings us to a similar conclusion: quality attributes have not been expressed, defined, let alone aligned. Other complementary causes can be added to the game, such as a lack of leadership, openness of management. We will get to that later.

The last why to explore is negotiation. Why having to negotiate and not just decide? Reality is catching up with us for several reasons. Stakeholders often find it difficult to prioritize their needs. It’s the typical “do it all !”. This ties in with the second constraint, that of limited resources. In addition, even with an unlimited budget, constraints remain incompressible and contradictory, requiring compromises. Negotiation is necessary because we cannot achieve everything.

Negotiating without a common basis is a waste of time; it is essential first to address first the root cause of quality alignment. Negotiation without preparation is risky most of the time; it is better to secure this step.

Preparing a negotiation upstream of collaborative workshops

Start with the end in mind is the second principle to follow in our exercise. A negotiation requires clear objectives allowing us to align our work priorities. In our case, this is the definition of quality in our context.

A common goal of Quality Engineering is to provide continuous and lasting value to the users of the product. It is this value that we must succeed in materializing for all stakeholders by translating it into their particular context. Preparation involves identifying the stakeholders, their level of interest, and their power over the topics you want to prioritize. This mapping will be helpful for you to plan and adapt the workshops according to the interlocutors.

The second step is to define our negotiating position using the acronyms BATNA (Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement) and ZOPA (Zone Of Potential Agreement), defining our acceptable position interval.

The objective of this exercise is not to predict the future but to help us to :

- Become aware of what we want to achieve

- Compare the priority of quality attributes between them

- Have a better perspective of trade-offs medium and long-term

- Better understand the value of quality and non-quality

Preparation is necessary to have an overall vision before going into the details of the workshops.

The third step is to prepare the content of the workshops. The objective is to materialize the attributes of quality related to the product; the supporting exercises must enable to map the different quality attributes in collaboration; physical or digital media should allow the insertion of elements in parallel to support an open sharing by each actor.

We can complete our approach with a Question Asker by preparing a list of questions to refine the actors’ understanding.

It is now time to organize Win-win workshops.

Aligning stakeholders around common interests

Seek first to understand before being understood is the third principle to apply. Iman Benlekehal shared the concept of Shift-Up & Spread, which illustrates well what we want to achieve: to align the actors on a commonly defined quality.

The purpose of collaborative models is to identify the expectations of the various stakeholders. We have to secure active listening, questioning, and reformulation to align a common vocabulary. Only then can a convergence exercise be carried out.

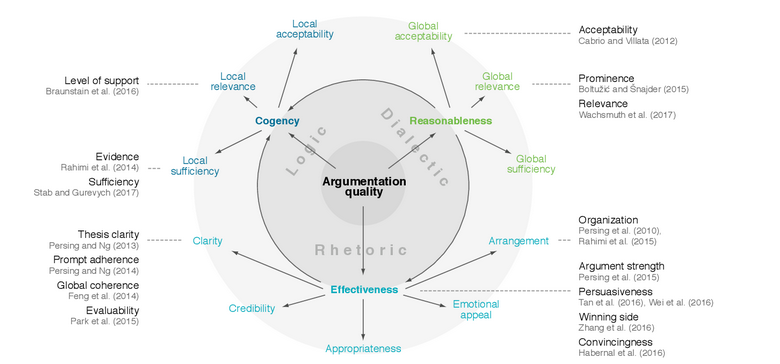

At this stage, the words “quality” or “tests” have not necessarily been mentioned; that is not the subject. Quality attribute models are helpful for a Cartesian approach and profiles navigating this ecosystem. The preparation of the workshops will have enabled you to identify the questions that the actors can omit. It is then your job to make the connection between expectations and quality attributes.

This work is the alignment of a quality strategy, far from an exercise carried out alone. Without realizing it, we naturally negotiated the quality budget. The purpose of the compilation work will be to define what to implement and measure during execution.

Our goal is effectively to bridge the gap between expected and actual value.

Define the value measures to be followed in the iterations

The implementation of Quality Engineering will constrain the software life cycle to meet the defined expectations. The ability to measure the creation of value to meet expectations is therefore necessary.

Value is like quality, subjective and contextual. However, one thing that organizations serving users have in common is that they seek to solve problems that users are willing to pay for. Their level of engagement, satisfaction, or purchase rate are therefore valuable measures.

Both local and global measures are relevant. Local measurements validate the added value of surgical actions. Global measurements help to ensure the contribution of local action to the system as a whole. We want to avoid negative local optimizations.

“If you deliberately downgrade quality, your team might go faster at first, but soon the demoralization of producing crap will overwhelm any gains you temporarily made from not testing, or not reviewing, or not sticking to standards.”

Kent Beck, Extreme Programming Explained.

Management is one of the key areas in driving a system towards its objectives. The natural tendency of the actors will be towards the gradual expansion of the perimeter to the detriment of the attributes initially defined. Measurement and corrective implementation is the role of the Quality actors. This goes through a good number of systematic practices.

Prioritizing is a fundamental practice. We must continually limit the volume of work and judge the relevance of the topics for the provision of value. Kanban, Limit WIP, and TQM within Agile planning practices are helpful to this effect. The retrospective mechanisms are useful for containing the complexity, debt, and surprises encountered in execution.

In some cases, we require a direct and more frontal negotiation.

What to do when the negotiation seems closed

Specific contexts are not favorable to the steps mentioned: a dictator manager, historical conflicts, the culture of the organization. Indeed, doing Quality is not easy, but what to do?

Play or Pass is a principle to choose our fights. Some approaches have too low a probability of success in particular contexts. It is better to know how to avoid the subject and come back to it when the context is more favorable, working your patience. The lack of quality ends up being felt sooner or later by the effect of technical debt, a tired team, etc. Indirect approaches then remain possible for the combats selected.

We can try to identify alarming metrics or other concrete malfunctions. Some relays or internal influencers can become ambassadors of the process, convincing them by arguments and even more by example. One approach can be to put decision-makers in a situation, having to make changes in software full of technical debt. An example is available here. If you are convinced of a subject and its implementation, what prevents you from demonstrating it, even if it means making an extra effort?

The success of this early TQM project team was sometimes invoked to demonstrate how TQM worked. ”

Joan E. Manley, Negotiating Quality

Emna and Zoé also shared the usefulness of gamification techniques for a team approach. These methods can be used both in the alignment phase and to indirectly promote quality. An example is this unit testing game shared by Zoe. Imagine that actors who demonstrated the value of quality obtain a visible recognition towards the team; it will make more than one think.

Be clear about what does not seem negotiable for the actors and for yourself. We can reach a situation where flying to other horizons is the only way out.

Before we get there, let’s stay combative and avoid mistakes on the course.

The negotiation mistakes to avoid

Most of the mistakes we have identified are due to a purely intuitive approach lacking methodology. In quality and engineering, purely technical approaches are also a common trap.

Forget the arguments starting with the tests to be carried out, manual or automated. Let us return to the introductory example of allocation of “30 % of the time to quality”. Would you accept a 30 % tax increase for “the quality of the country”? Probably not; some arguments are needed. Putting yourself in the shoes of the stakeholders is therefore fundamental to articulate a value proposition.

We come to the second trap, adopting a frontal approach without listening or preparing for the exchange. We will seek to push for solutions without having understood the problems and needs of our interlocutors. It is a waste of time, or at least ineffective. This tactic often materializes a lack of understanding; quality requires lasting influence and processes.

In conclusion, a “lightning raid” operation will not work.

The negotiation of quality is that of shared value

Our initial question was to identify actionable practices to negotiate a project budget allocated to quality. The initial lack of budget is often caused by a lack of alignment of quality attributes. Our discussion led us to that of the definition of a shared value.

The exploration of the why highlighted the need for a structured process to naturally translate quality into deliverables:

- Preparation of our negotiation and workshops

- Animation of collaborative sharings between the various stakeholders

- Alignment of the value to be created and of its measurement during iterations

Following the example of retrospectives with a learning goal, we have also identified the good practices and errors to avoid negotiating quality. We will remember the lack of preparation as a recurring cause.

Negotiation is an art mixing human and technical skills, like Quality Engineering. Emna launched the debate on the importance of this skill on the forum of the Ministry of Testing.

Quality, like trust, is gained over time. However, let’s stay proactive as we do not have months ahead to change.

References

Joan E. Manley, Negotiating Quality: Total Quality Management and the Complexities of Transforming Professional Organizations, JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/684806.pdf